Israel: Nakba and Return

1948: two generations of Palestinian refugees

The Zionist dream is known as the “Ingathering of Exiles.” Of course, this means Jewish exiles. But there will come a time for another ingathering of exiles. Those who were exiled in 1948. The Palestinians.

In the Zionist narrative, 1948 marked the definitive victory of Zionism and the creation of the Jewish state. Everything that came after ratified this happy vision of the return of the Jews to “our land” or, as the stirring (to Jews) cadences of the national anthem put it:

To be a free people in our land,

In the land of Zion, Jerusalem.

But again, this triumphalist narrative leaves out one inconvenient fact: those 1-million refugees. Arik Arielpublished an essay in Haaretz’s Hebrew edition (this post summarizes the article and adds my own analysis which diverges from Ariel in some points) on the aftermath of Nakba in Israeli history. In other words, how did the Israeli government deal with the “problem” of the forced exile of over half of the 1948 Palestinian residents of Israel? Contrary to what one may believe, Israel and the international community did not forget about the refugees after the former rid itself of them in ’48. In fact, the government appointed committees, conducted top secret cabinet deliberations, and entertained numerous plans developed by the United Nations, the State Department, and other bodies.

Again, contrary to common belief, Israel did not dismiss out-of hand-proposals which included Israeli acceptance of significant numbers of returning refugees. In fact, a number of Israeli governments accepted the notion that they would have to do so as part of any final resolution of the issue.

Let’s set the background with some statistics: though estimates vary depending on which historian you ask, I’m using the following ones to give you an overall sense of the proportion of Jews and Palestinians who lived, and live in Israel. Before 1948, there were approximately 950,000 Palestinians (other historians put the number as high as 1.3-million) living in what became Israel. There were about 650,000 Jews. During the War, 80% of the Palestinians were expelled, leaving about 150,000. After the 1948 war, the overall population of Israel was 800,000. Israeli Palestinians were just over 20% of the total.

Ariel notes, this week marked the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Pres. Kennedy. He uses this historical landmark to segue to a crucial get-acquainted meeting between Kennedy and then-Prime Minister David Ben Gurion in 1961. At that first meeting between the two leaders, Ben Gurion heard a number of things that disturbed him. One was that the new administration proposed to address and resolve the refugee issue.

By that date, Israel’s population was 2.1 million (Haaretz mistakenly puts this number at 3.1-million, either a typo or error). Of this, 250,000 were Israeli Palestinian, or 11.3% of the total.

In preparation for deliberations in the United Nations, and a plan being prepared by the State Department, the then-Labor government held a secret meeting at which it discussed what were its red lines (Ariel uses the phrase, “the price Israel could live with”) concerning the Palestinian exiles. Yosef Burg (Avram Burg’s father), long-time National Religious Party minister, spoke quite crudely about the Palestinian question being not only an “atomic bomb” but an “anatomical bomb.”

Levi Eshkol, then minister of the treasury and later prime minister, asked what would be considered a decisive Jewish majority. He found that 70% could certainly be considered decisive. In other words, he was tacitly admitting Israel could comfortably absorb up to three times the number of Palestinian citizens as it then had. Ben Gurion disagreed and said that if there were 600,000 Palestinians in Israel, within two generations they would be a majority. He actually turned out to be right. Today, fifty years later, there are more Palestinians than Jews in the area including Israel and the Territories. Of course, no formal decisions arose from any of the cabinet discussion.

The foreign ministry, in its own set of secret deliberations, believed Israel could absorb 40,000 refugees within a three-four year period without constituting any great danger. Others felt that Israel could “live with” a population that was 25% Palestinian (currently just over 20% of Israelis are Palestinian).

Israel seems to have expected the world might agree to do a sort of “swap,” by which acceptance of refugees would be “balanced” by Palestinian-Israeli citizens who would be persuaded to emigrate. This was intended to ‘protect’ the Jewish majority, so that it would not be “overwhelmed” by the burgeoning Palestinian birthrate (compared to the lower Jewish birthrate).

Already in the midst of the 1948 War, the Jewish Agency established a “Transfer Committee,” whose mandate was to devise a policy concerning the refugees. One of its main thrusts was to create the impression that their expulsion was permanent. There was to be no going back. That is why Israel, by law, refused to allow refugees to return and confiscated their property (those expelled left behind 40-million dunams of land and 8,000 stores and businesses).

The committee believed the best solution was to encourage the refugees to resettle and support them (financially) in this. It also recommended encouraging the remaining population to emigrate, destroying remaining Palestinian villages (something like what is currently happening to the Negev Bedouin), and preventing new development of existing Palestinian-owned land. Many of these recommendations were enacted and remain de facto government policy.

Another official voice reveals much about government attitudes. In 1950, Moshe Dayan, then IDF commander of southern front said:

We should relate to the remaining 150,000 Arabs in Israel as if their fate is not yet sealed. I hope that in the years to come there will be more possibilities to conduct [population] transfer from the land of Israel.

Official government deliberations among the military and political echelon reveal that they hoped that many of the remaining Palestinians would “draw the proper conclusion” from their loss in the “War of Independence” and emigrate willingly. Some even deluded themselves into believing that Palestinians were eager to leave if they could dispose of their property. They suggested that Palestinian Christians would to to Lebanon and Muslims to Egypt. And that there might be a way to negotiate a deal whereby the property of Arabs Jews fleeing to Israel could be exchanged for the property of Palestinians leaving Israel. Though the scheme seems outlandish today, those who discussed it thought it quite practicable.

But as senior a figure as Defense Minister Pinchas Lavon speaking in 1953 realized that emigration resolved only part of the problem since the Palestinian population increased naturally by 6,000 each year. No amount of voluntary emigration could offset that.

That’s why Israel devised even wackier plans. Like the one to “transfer” the Palestinian Christians in the Galilee to Argentina and Brazil in a plan code-named ‘Operation Yochanan.’ It was named for an Israelite leader of one of the revolts against Rome who was a native of Gush Halav, a modern Palestinian village in the region. Ironically, but perhaps not surprisingly, Moshe Sharett, known at the time as a decided political dove, was the primary backer of this project. The Jewish Agency in Argentina was directed to prepare funds to pay Palestinians who resettled on Argentine farmland. The project was to be described publicly as an initiative of the Palestinian community itself.

But in 1953, the Argentine government blessedly got cold feet and Project Jonathan was canceled. That did not cancel ongoing and concerted efforts by the ministry of foreign affairs to identify other places where Palestinian citizens could emigrate and funds to encourage them to do so. In fact, in 1950 the ministry proposed sending Palestinians to Libya and Somalia in exchange for the 18,000 Jews who emigrated from these countries to Israel during that period. In 1955, a senior Israeli official even traveled to Libya and Algeria to explore the possibility of resettling Palestinian refugees and those Palestinians willing to emigrate from Israel itself. They would replace the Jews who were emigrating from those countries to Israel.

A different Israeli official attempted to buy 100,000 dunams in Libya for resettling refugees. This plan too was scuttled when word leaked to the media and Libya’s ruler was pressured to end it. In 1956, a different plan was developed called “Uri” which was to settle 75 refugee families on a Libyan farm. The plan even included a Swiss front company that was intended to handle all the purchases to preserve Israel’s “cover.” This too was leaked to the media and died. In 1959, another plan named “Theo” proposed to resettle 2,000 refugee families in Libya. Those who originated it estimated it would require $11.5-million to execute (a huge sum at that time). There were similar schemes to buy property in Cyprus for this purpose.

As late as the 1960's the foreign ministry continued to hatch plans to encourage refugees to move to Europe, specifically France and Germany. The latter especially, in that era, was known to have a labor shortage which these new hands would assist. It also explored such opportunities in Austria and Switzerland. These projects were known by the common name, ‘Operation Worker.’

There were consultations with the government of Iraq in which it would accept Palestinian refugees in exchange for the 140,000 Iraqi Jews who fled to Israel. This plan never came to fruition because Israeli ministers worried that the fleeing Jews would demand reparations for the property they were forced to leave behind. This might make the Palestinians realize that they too should lodge demands to compensate them for their losses. That was a hornet’s nest into which Israeli officials didn’t want to stick their hands.

These various plans didn’t finally end until after the 1967 War.

Returning to the Kennedy administration’s efforts to solve the refugee problem. Israel finally agreed in principle to accept the return of up to 10% of the refugees as part of a comprehensive agreement. When other western nations refused to endorse the idea, this plan too was dropped. Gradually, Israel felt less and less need to address the issue, especially as matters heated up in the refugees camps themselves with the founding of the Fatah movement and the move toward greater militancy on the part of the Palestinians themselves. At that point, the refugees were transformed from a humanitarian matter, to a matter of Palestinian nationhood.

Ariel points out that Israel, in an era when its demographic and geo-strategic situation was far worse than it is today, declared its willingness to return far more refugees than it ever agreed to in recent decades. This should teach us that Israel’s current rejectionnist stance was not always thus. Further, it should not be seen as a position Israel has maintained historically over the full course of its history. There were Israeli governments far more accommodating and realistic than recent ones.

Move Over Nakba, Naksa is Here

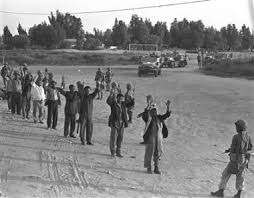

Palestinians surrender during Naksa, 1967 War

Until a few years ago, it seemed that the narrative of the Israeli-Arab conflict was determined mostly by Israel: there was the miraculous vote in the UN General Assembly recognizing the partition. Then the even more miraculous 1948 War of Independence, which established the State of Israel. Yes, there was the momentary setback of the 1956 Suez War, whose victorious territorial prize of the Sinai was wrenched from Israel’s hands by Pres. Dwight Eisenhower. But the Lord’s miracles continued in 1967 as Israel reunited the nation’s eternal capital, Jerusalem. The sparks of Messianic redemption were also sown by the return to our Biblical ancestral lands in places that came to be called by many in Israel, Judea and Samaria. Israel affirmed its rendez-vous with Jewish destiny by returning its sons and daughters to these Biblical holy places in Shechem and Hebron, where they became latter-day versions of the pioneers of the 1920s who “cleared the land and drained the swamps.”

There wasn’t much room in all this history, destiny, and messianic redemption for the narrative of the “loser.” Israelis, the most humane among them, could afford to acknowledge the sins that enabled the triumphs of Israel. These visionaries bucked the national consensus, but they were swimming upstream and against the prevailing winds. Over time, their voice became thinner and thinner until it was mostly snuffed out in the shouts of triumph from the Israeli nationalist camp.

But over the past decade or more, the tables have turned. With the onset of the Intifadas, Palestinians began to make a claim to a narrative of their own. It wasn’t just a story they proclaimed for themselves. They asked the rest of the world to acknowledge it as well. Slowly, ever so slowly, the world has turned from intense admiration of Israel’s achievements to recognition of the moral cost of those victories.

In the past 11 years, we have gone through two Intifadas, wars in Gaza in (2009) and Lebanon (2006). With each of these new developments in the Palestinian national struggle, Israel’s narrative receded and the Palestinian’s advanced.

Though the term Nakba has existed for decades, few outside the Arab world have been willing to acknowledge either it or the historical event it denotes. Until now. The historical truth of this tragedy can no longer be mitigated or denied as it has been for so long. Israel has tried to stick its finger in the dyke in order to suppress awareness. It was sung the praises of its own national myth attempting to drown out those who paid the price for Israel’s joy. But there is about the Nakba, what James Joyce called an “ineluctable modality of the visible,” something which can no longer be denied, a fundamental truth that has been repressed far too long.

Now, the tender shoots of the Arab Spring have burst forth. On Nakba Day last month, Palestinian supporters overwhelmed four Israeli borders demanding that the injustice of the Nakba be redressed. Tomorrow, many of these same protesters will do it again, this time to commemorate the Palestinian loss represented by the 1967 War. They’re calling it Naksa, the Setback. Perhaps slightly less tragic than Nakba, or Catastrophe. But the aggregation of these terms strengthens the sense of a wrong that cannot be denied.

News stories today indicate that Hezbollah has asked for protests on the Lebanese border be cancelled. So we don’t quite know what the dimensions of the event will be. But there is one thing of which you can be sure. The dimensions of this struggle will grow day by day, protest by protest. And as they do, Israel’s case will grow weaker and weaker.

Later this month, a Turkish flotilla consisting of peace activists from the Arab world along with Israelis and American Jews will set sail for Gaza. This voyage is a follow-up to the Mavi Marmara catastrophe in which Israeli commandos killed nine Turks last year. Turkish media reports that the U.S. has dangled a carrot in front of the Turkish government, promising to host an Israeli-Palestinian peace conference in Turkey if it will call off the flotilla and normalize relations with Israel.

The very notion of such a bribe is insulting both to Turkey and to the Israeli-Arab peace process. Can a nation be bought? Can peace be bought? For a mess of porridge? What does Obama take Turkey for? This is a proud nation that can’t be taken in by charades. Its leader, Pres. Erdogan is no fool. He ought to tell the U.S. and Israel that it knows what the price of peace is and when those two are ready to pay, then they have his phone number, as Secretary of State Baker said during the Bush administration, and should call. Until then, they should stop wasting everyone’s time with makeshift measures and blandishments like peace conferences. What good is such a meeting when Israel isn’t ready to deal?

As I wrote in my latest contribution to Truthout, a September date with destiny is looming for Palestine in the UN General Assembly. This is yet another incremental advance of the cause of Palestine and another nail in the coffin of the Occupation. From my reading of UN processes, the Security Council can delay but not deny Palestinian statehood. It’s only a matter of time. As Meir Dagan has been saying lately, time is not on Israel’s side. The longer it delays the worse the deal it will get.

I should make clear that I’m not talking about erasing the Israeli narrative or expecting Israelis to grovel at the feet of those they’ve injured. The Israeli narrative is still valid. All those achievements are laudable, something Israel and the Jewish people can be proud of. But not at the expense of Palestine. Not if Palestine must be denied. What the world demands is that there be two legitimate narratives neither of which eclipses or demeans the other. Twoequal narratives. When Bibi Netanyahu or whoever is the Israeli PM at the time can do that, he knows Mahmoud Abbas’s phone number. He can call.

No comments:

Post a Comment