Israel and Judah were related Iron Age kingdoms of the ancient Levant. The Kingdom of Israel emerged as an important local power by the 9th century BCE before falling to the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 722 BCE. Israel's southern neighbor, the Kingdom of Judah, emerged in the 8th century BCE[1] and enjoyed a period of prosperity as a client-state of first Assyria and then Babylon before a revolt against the Neo-Babylonian Empire led to its destruction in 586 BCE. Following the fall of Babylon to the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, some Judean exiles returned to Jerusalem, inaugurating the formative period in the development of a distinctive Judahite identity in the Persian province of Yehud. Yehud was absorbed into the subsequent Hellenistic kingdoms that followed the conquests of Alexander the Great, but in the 2nd century BCE the Judaeans revolted against the Hellenist Seleucid Empire and created the Hasmonean kingdom. This, the last nominally independent Judean kingdom, came to an end in 63 BCE with its conquest by Pompey of Rome. With the installation of client kingdoms under the Herodian Dynasty, the Kingdom of Israel was wracked by civil disturbances which culminated in the First Jewish–Roman War, the destruction of the Temple, the emergence of Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity.

Periods

- Iron Age I: 1200–1000

- Iron Age II: 1000–586

- Neo-Babylonian: 586–539

- Persian: 539–332

- Hellenistic: 332–53[2]

Late Bronze Age Background (1600–1200 BCE)

The Canaanite god Ba'al, 14th–12th century BCE (Louvre museum, Paris)

The eastern Mediterranean seaboard – theLevant – stretches 400 miles north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai desert, and 70 to 100 miles east to west between the sea and the Arabian desert.[3] The coastal plain of the southern Levant, broad in the south and narrowing to the north, is backed in its southernmost portion by a zone of foothills, the Shephelah; like the plain this narrows as it goes northwards, ending in the promontory of Mount Carmel. East of the plain and the Shephelah is a mountainous ridge, the "hill country of Judah" in the south, the "hill country of Ephraim" north of that, then Galilee and the Lebanon mountains. To the east again lie the steep-sided valley occupied by the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the wadi of the Arabah, which continues down to the eastern arm of the Red Sea. Beyond the plateau is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, to the northeast Mesopotamia. The location and geographical characteristics of the narrow Levant made the area a battleground among the powerful entities that surrounded it.[4]

Canaan in the Late Bronze Age was a shadow of what it had been centuries earlier: many cities were abandoned, others shrank in size, and the total settled population was probably not much more than a hundred thousand.[5] Settlement was concentrated in cities along the coastal plain and along major communication routes; the central and northern hill country which would later become the biblical kingdom of Israel was only sparsely inhabited[6] although letters from the Egyptian archives indicate that Jerusalem was already a Canaanite city-state recognising Egyptian overlordship.[7] Politically and culturally it was dominated by Egypt,[8] each city under its own ruler, constantly at odds with its neighbours, and appealing to the Egyptians to adjudicate their differences.[6]

The Canaanite city-state system broke down at the end of the Late Bronze period,[9]and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into that of the Philistines, Phoenicians and Israelites.[10] The process was gradual, rather than swift,[11] and a strong Egyptian presence continued into the 12th century BCE, and, while some Canaanite cities were destroyed, others continued to exist in Iron Age I.[12]

Iron Age I (1200–1000 BCE)

The Merneptah stele. While alternative translations exist, the majority ofbiblical archeologists translate a set of hieroglyphs as "Israel", representing the first instance of the name Israel in the historical record.

The name "Israel" first appears in the stele of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah c. 1209 BCE: "Israel is laid waste and his seed is no more."[13] This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity of the central highlands, well enough established for the Egyptians to perceive it as a possible challenge to their hegemony, but an ethnic group rather than an organised state;[14]Archaeologist Paula McNutt says: "It is probably ... during Iron Age I [that] a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite'," differentiating itself from its neighbours via prohibitions onintermarriage, an emphasis on family history andgenealogy, and religion.[15]

In the Late Bronze Age there were no more than about 25 villages in the highlands, but this increased to over 300 by the end of Iron Age I, while the settled population doubled from 20,000 to 40,000.[16] The villages were more numerous and larger in the north, and probably shared the highlands with pastoral nomads, who left no remains.[17] Archaeologists and historians attempting to trace the origins of these villagers have found it impossible to identify any distinctive features that could define them as specifically Israelite – collared-rim jars and four-room houses have been identified outside the highlands and thus cannot be used to distinguish Israelite sites,[18] and while the pottery of the highland villages is far more limited than that of lowland Canaanite sites, it develops typologically out of Canaanite pottery that came before.[19] Israel Finkelstein proposed that the oval or circular layout that distinguishes some of the earliest highland sites, and the notable absence of pig bones from hill sites, could be taken as markers of ethnicity, but others have cautioned that these can be a "common-sense" adaptation to highland life and not necessarily revelatory of origins.[20] Other Aramaean sites also demonstrate a contemporary absence of pig remains at that time, unlike earlier Canaanite and later Philistine excavations.

In The Bible Unearthed (2001), Finkelstein and Silberman summarised recent studies. They described how, up until 1967, the Israelite heartland in the highlands of western Palestine was virtually an archaeological terra incognita. Since then, intensive surveys have examined the traditional territories of the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim, and Manasseh. These surveys have revealed the sudden emergence of a new culture contrasting with the Philistine and Canaanite societies existing in the Land of Israel earlier during Iron Age I.[21] This new culture is characterised by a lack of pork remains (whereas pork formed 20% of the Philistine diet in places), by an abandonment of the Philistine/Canaanite custom of having highly decorated pottery, and by the practice of circumcision. The Israelite ethnic identity had originated, not from the Exodus and a subsequent conquest, but from a transformation of the existing Canaanite-Philistine cultures.[22]

These surveys revolutionized the study of early Israel. The discovery of the remains of a dense network of highland villages — all apparently established within the span of few generations — indicated that a dramatic social transformation had taken place in the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE. There was no sign of violent invasion or even the infiltration of a clearly defined ethnic group. Instead, it seemed to be a revolution in lifestyle. In the formerly sparsely populated highlands from the Judean hills in the south to the hills of Samaria in the north, far from the Canaanite cities that were in the process of collapse and disintegration, about two-hundred fifty hilltop communities suddenly sprang up. Here were the first Israelites.[23]

From then on, over a period of hundreds of years until after the return of the exiles from Babylon, the Israelites and other tribes gradually absorbed the Canaanites. After the period of Ezra (~450 BCE) there is no more biblical record of them.[24] TheHebrew language, a dialect of Canaanite, became the language of the hill country, and later of the valleys and plains.[25]

Modern scholars therefore see Israel arising peacefully and internally from existing people in the highlands of Canaan.[26]

Iron Age II (1000–587 BCE)

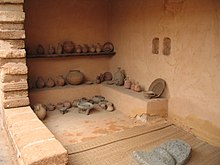

A reconstructed Israelite house, 10th–7th century BCE. Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv.

Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.[27] In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital,[27] possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I, the biblical Shishak, records a series of campaigns directed at the area.[28] Israel had clearly emerged by the middle of the 9th century BCE, when the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III names "Ahabthe Israelite" among his enemies at the battle of Qarqar (853). At this time Israel was apparently engaged in a three-way contest with Damascus and Tyre for control of the Jezreel Valley and Galilee in the north, and with Moab, Ammon and Damascus in the east for control of Gilead;[27] the Mesha stele (c. 830), left by a king of Moab, celebrates his success in throwing off the oppression of the "House of Omri" (i.e., Israel). It bears what is generally thought to be the earliest extra-biblical Semiticreference to the name Yahweh (YHWH), whose temple goods were plundered by Mesha and brought before his own god Kemosh.

French scholar André Lemaire has reconstructed a portion of line 31 of the stele as mentioning the "House of David".[28] [29] Other scholars disagree, saying that BYTDWD is a place name not a dynasty.[30] The Tel Dan stele (c. 841) tells of the death of a king of Israel, probably Jehoram, at the hands of a king of Aram Damascus.[28] A century later Israel came into increasing conflict with the expandingneo-Assyrian empire, which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722). Both the biblical and Assyrian sources speak of a massive deportation of people from Israel and their replacement with settlers from other parts of the empire – such population exchanges were an established part of Assyrian imperial policy, a means of breaking the old power structure – and the former Israel never again became an independent political entity.[31]

Judah emerged somewhat later than Israel, probably during the 9th century BCE, but the subject is one of considerable controversy.[1] There are indications that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the southern highlands had been divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy.[32] During the reign ofHezekiah, between c. 715 and 686 BCE, a notable increase in the power of theJudean state can be observed.[33] This is reflected in archaeological sites and findings, such as the Broad Wall; a defensive city wall in Jerusalem; and the Siloam Tunnel, an aqueduct designed to provide Jerusalem with water during an impending siege by the Assyrians led by Sennacherib; and the Siloam Inscription, a lintel inscription found over the doorway of a tomb, has been ascribed to comptroller Shebna. LMLK seals on storage jar handles, excavated from strata in and around that formed by Sennacherib's destruction, appear to have been used throughout Sennacherib's 29-year reign, along with bullae from sealed documents, some that belonged to Hezekiah himself and others that name his servants;[34]

King Ahaz's Seal is a piece of reddish-brown clay that belonged to King Ahaz of Judah, who ruled from 732 to 716 BCE. This seal contains not only the name of the king, but the name of his father, King Yehotam. In addition, Ahaz is specifically identified as "king of Judah." The Hebrew inscription, which is set on three lines, reads as follows: "l'hz*y/hwtm*mlk*/yhdh", which translates as "belonging to Ahaz (son of) Yehotam, King of Judah."[35]

In the 7th century Jerusalem grew to contain a population many times greater than earlier and achieved clear dominance over its neighbours.[36] This occurred at the same time that Israel was being destroyed by Assyria, and was probably the result of a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian vassal controlling the valuable olive industry.[36] Judah prospered as an Assyrianvassal state (despite a disastrous rebellion against Sennacherib), but in the last half of the 7th century BCE Assyria suddenly collapsed, and the ensuing competition between the Egyptian and Neo-Babylonian empires for control of the land led to the destruction of Judah in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582.[36]

Babylonian period

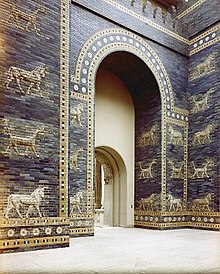

Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate ofBabylon

Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population[37] and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours.[38] Jerusalem, while probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the town of Mizpah in Benjaminin the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of Yehud Medinata.[39] (This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of Ashkalon was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite [but not the bulk of the population] was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location).[40] There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at Bethel in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.[41]

The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, but the liquidation of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries.[42] The most significant casualty was the state ideology of "Zion theology,"[43] the idea that the god of Israel had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the Davidic dynasty would reign there forever.[44] The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community – kings, priests, scribes and prophets – to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics.[45] The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew Bible: Isaiah 40–55; Ezekiel; the final version of Jeremiah; the work of the hypothesized priestly source in the Pentateuch; and the final form of the history of Israel from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings.[46] Theologically, the Babylonian exiles were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world) and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness.[46] Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of Hebrew identity distinct from other peoples,[47] with increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to sustain that distinction.[48]

The concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises the fact that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before.[49] It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon.[50] The assassination around 582 of the Babylonian governor by a disaffected member of the former royal House of David provoked a Babylonian crackdown, possibly reflected in the Book of Lamentations, but the situation seems to have soon stabilised again.[51] Nevertheless, those unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs by Samaritans, Arabs, and Ammonites.[52]

Persian period

When Babylon fell to the Persian Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, Judah (or Yehud medinata, the "province of Yehud") became an administrative division within thePersian empire. Cyrus was succeeded as king by Cambyses, who added Egypt to the empire, incidentally transforming Yehud and the Philistine plain into an important frontier zone. His death in 522 was followed by a period of turmoil untilDarius the Great seized the throne in about 521. Darius introduced a reform of the administrative arrangements of the empire including the collection, codification and administration of local law codes, and it is reasonable to suppose that this policy lay behind the redaction of the Jewish Torah.[53] After 404 the Persians lost control of Egypt, which became Persia's main rival outside Europe, causing the Persian authorities to tighten their administrative control over Yehud and the rest of the Levant.[54] Egypt was eventually reconquered, but soon afterward Persia fell toAlexander the Great, ushering in the Hellenistic period in the Levant.

Yehud's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000 and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple.[55] According to the biblical history, one of the first acts ofCyrus, the Persian conqueror of Babylon, was to commission Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their Temple, a task which they are said to have completed c. 515.[56] Yet it was probably not until the middle of the next century, at the earliest, that Jerusalem again became the capital of Judah.[57] The Persians may have experimented initially with ruling Yehud as a Davidic client-kingdom under descendants of Jehoiachin,[58] but by the mid–5th century BCE, Yehud had become, in practice, a theocracy, ruled by hereditary high priests,[59] with a Persian-appointed governor, frequently Jewish, charged with keeping order and seeing that taxes (tribute) were collected and paid.[60] According to the biblical history, Ezra andNehemiah arrived in Jerusalem in the middle of the 5th century BCE, the former empowered by the Persian king to enforce the Torah, the latter holding the status of governor with a royal commission to restore Jerusalem's walls.[61] The biblical history mentions tension between the returnees and those who had remained in Yehud, the returnees rebuffing the attempt of the "peoples of the land" to participate in the rebuilding of the Temple; this attitude was based partly on the exclusivism that the exiles had developed while in Babylon and, probably, also partly on disputes over property.[62] During the 5th century BCE, Ezra and Nehemiah attempted to re-integrate these rival factions into a united and ritually pure society, inspired by the prophecies of Ezekiel and his followers.[63]

The Persian era, and especially the period between 538 and 400 BCE, laid the foundations for the unified Judaic religion and the beginning of a scriptural canon.[64]Other important landmarks in this period include the replacement of Hebrew as the everyday language of Judah by Aramaic (although Hebrew continued to be used for religious and literary purposes)[65] and Darius's reform of the empire's bureaucracy, which may have led to extensive revisions and reorganizations of the Jewish Torah.[53] The Israel of the Persian period consisted of descendants of the inhabitants of the old kingdom of Judah, returnees from the Babylonian exile community, Mesopotamians who had joined them or had been exiled themselves to Samaria at a far earlier period, Samaritans, and others.[66]

Hellenistic period

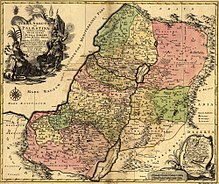

The Hasmonean kingdom at its largest extent

On the death of Alexander the Great (322 BCE), Alexander's generals divided the empire among themselves. Ptolemy I, the ruler of Egypt, seizedYehud Medinata, but his successors lost it in 198 to the Seleucids of Syria. At first, relations between Seleucids and Jews were cordial, but the attempt of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (174–163) to impose Hellenic cults on Judea sparked anational rebellion that ended in the expulsion of the Seleucids and the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under theHasmonean dynasty. Some modern commentators see this period also as a civil war between orthodox and hellenized Jews.[67] [68]Hasmonean kings attempted to revive the Judah described in the Bible: a Jewish monarchy ruled from Jerusalem and including all territories once ruled by David and Solomon. In order to carry out this project, the Hasmoneans forcibly converted one-time Moabites, Edomites, and Ammonites to Judaism, as well as the lost kingdom of Israel.[69] Some scholars argue that the Hasmonean dynasty institutionalized the final Jewish biblical canon.[70]

In 63 BCE the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem and made the Jewish kingdom a client state of Rome. In 40–39 BCE, Herod the Great was appointed King of the Jews by the Roman Senate, and in 6 CE the last ethnarch of Judea was deposed by the emperor Augustus, his territories combined with Idumea andSamaria and annexed as Iudaea Province under direct Roman administration.[71] The name Judea (Iudaea) ceased to be used by Greco-Romans after the revolt of Simon Bar Kochba in 135 CE; the area was henceforth called Syria Palaestina (Greek: Παλαιστίνη, Palaistinē; Latin: Palaestina).

Religion

Iron Age Yahwism

The religion of the Israelites of Iron Age I, like the Ancient Canaanite religion from which it evolved and other religions of the ancient Near East, was based on a cult of ancestors and worship of family gods (the "gods of the fathers").[72] [73] With the emergence of the monarchy at the beginning of Iron Age II the kings promoted their family god, Yahweh, as the god of the kingdom, but beyond the royal court, religion continued to be both polytheistic and family-centered.[74] The major deities were not numerous – El, Asherah, and Yahweh, with Baal as a fourth god, and perhapsShamash (the sun) in the early period.[75] At an early stage El and Yahweh became fused and Asherah did not continue as a separate state cult,[75] although she continued to be popular at a community level until Persian times.[76]

Yahweh, the national god of both Israel and Judah, seems to have originated inEdom and Midian in southern Canaan and may have been brought to Israel by theKenites and Midianites at an early stage.[77] There is a general consensus among scholars that the first formative event in the emergence of the distinctive religion described in the Bible was triggered by the destruction of Israel by Assyria in c. 722 BCE. Refugees from the northern kingdom fled to Judah, bringing with them laws and a prophetic tradition of Yahweh. This religion was subsequently adopted by the landowners of Judah, who in 640 BCE placed the eight-year-old Josiah on the throne. Judah at this time was a vassal state of Assyria, but Assyrian power collapsed in the 630s, and around 622 Josiah and his supporters launched a bid for independence expressed as loyalty to "Yahweh alone". Judah's independence was expressed in the law-code in the Book of Deuteronomy, written as a treaty between Judah and Yahweh to replace the vassal-treaty with Assyria.[78]

The Babylonian exile and Second Temple Judaism

According to the Deuteronomists, as scholars call these Judean nationalists, the treaty with Yahweh would enable Israel's god to preserve both the city and the king in return for the people's worship and obedience. The destruction of Jerusalem, its Temple, and the Davidic dynasty by Babylon in 587/586 BCE was deeply traumatic and led to revisions of the national mythos during the Babylonian exile. This revision was expressed in the Deuteronomistic history, the books of Joshua. Judges, Samueland Kings, which interpreted the Babylonian destruction as divinely-ordained punishment for the failure of Israel's kings to worship Yahweh to the exclusion of all other deities.[78]

The Second Temple period (520 BCE – 70 CE) differed in significant ways from what had gone before.[79] Strict monotheism emerged among the priests of the Temple establishment during the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, as did beliefs regardingangels and demons.[80] At this time, circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath-observance gained more significance as symbols of Jewish identity, and the institution of the synagogue became increasingly important. According to thedocumentary hypothesis, most of the Torah was written during this time.[81]

See also

- Biblical archaeology

- Chronology of the Bible

- Early Israelite campaigns

- Habiru

- History of Israel

- History of the Jews in Egypt

- History of the Jews in Iran

- History of the Jews in the Roman Empire

- History of the Southern Levant

- Intertestamental period

- Jew

- Jewish diaspora

- Lachish relief

- List of the Kings of Israel

- List of the Kings of Judah

- Old Testament

- Shasu

- Tanakh

- United Monarchy

References

Citations

- Grabbe 2008, pp. 225–6.

- King & Stager 2001, p. xxiii.

- Miller 1986, p. 36.

- Coogan 1998, pp. 4–7.

- Finkelstein 2001, p. 78.

- Killebrew 2005, pp. 38–9.

- Cahill in Vaughn 1992, pp. 27–33.

- Kuhrt 1995, p. 317.

- Killebrew 2005, pp. 10–6.

- Golden 2004b, pp. 61–2.

- McNutt 1999, p. 47.

- Golden 2004a, p. 155.

- Stager in Coogan 1998, p. 91.

- Dever 2003, p. 206.

- McNutt 1999, pp. 35.

- McNutt 1999, pp.46-47.

- McNutt 1999, p. 69.

- Miller 1986, p. 72.

- Killebrew 2005, p. 13.

- Edelman in Brett 2002, p. 46-47.

- Finkelstein and Silberman (2001) Free Press, New York, p. 107, ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- Avraham Faust (2009) "How Did Israel Become a People? The Genesis of Israelite Identity. Biblical Archaeology Review 201: pp. 62-69, 92-94

- Finkelstein and Silberman (2001), p. 107

- Holy Bible. King James version. Ezra, Chapter 9

- "Canaan".

- Compare: Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Journal for the study of the Old Testament: Supplement series. 241. Sheffield: A&C Black. p. 31. ISBN 9781850756576. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

Out of the discussions a new model is beginning to emerge, which has been inspired, above all, by recent archaeological field research. There are several variations in this new theory, but they share in common the image of an Israelite community which arose peacefully and internally in the highlands of Palestine.

- Thompson 1992, p. 408.

- Mazar in Finkelstein 2007, p. 163.

- Biblical Archaeology Review [May/June 1994], pp. 30–37

- "TelDan". vridar.info. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Lemche 1998, p. 85.

- Lehman in Vaughn 1992, p. 149.

- David M. Carr, Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature, Oxford University Press, 2005, 164.

- "LAMRYEU-HNNYEU-OBD-HZQYEU".

- First Impression: What We Learn from King Ahaz’s Seal (#m1), by Robert Deutsch, Archaeological Center.

- Thompson 1992, pp. 410–1.

- Grabbe 2004, p. 28.

- Lemaire in Blenkinsopp 2003, p. 291.

- Davies 2009.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 48.

- Blenkinsopp in Blenkinsopp 2003, pp. 103–5.

- Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 228.

- Middlemas 2005, pp. 1–2.

- Miller 1986, p. 203.

- Middlemas 2005, p. 2.

- Middlemas 2005, p. 10.

- Middlemas 2005, p. 17.

- Bedford 2001, p. 48.

- Barstad 2008, p. 109.

- Albertz 2003a, p. 92.

- Albertz 2003a, pp. 95–6.

- Albertz 2003a, p. 96.

- Blenkinsopp 1988, p. 64.

- Lipschits in Lipschits 2006, pp. 86–9.

- Grabbe 2004, pp. 29–30.

- Nodet 1999, p. 25.

- Davies in Amit 2006, p. 141.

- Niehr in Becking 1999, p. 231.

- Wylen 1996, p. 25.

- Grabbe 2004, pp. 154–5.

- Soggin 1998, p. 311.

- Miller 1986, p. 458.

- Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 229.

- Albertz 1994, pp. 437–8.

- Kottsieper in Lipschits 2006, pp. 109–10.

- Becking in Albertz 2003b, p. 19.

- Weigel, David. "Hanukkah as Jewish civil war - Slate Magazine". Slate.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- "The Revolt of the Maccabees". Simpletoremember.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- Davies 1992, pp. 149–50.

- Philip R. Davies in The Canon Debate, page 50: "With many other scholars, I conclude that the fixing of a canonical list was almost certainly the achievement of the Hasmonean dynasty."

- Ben-Sasson 1976, p. 246.

- Tubbs, Jonathan (2006)"The Canaanites" (BBC Books)

- Van der Toorn 1996, p.4.

- Van der Toorn 1996, p. 181–2.

- Smith 2002, p. 57.

- Dever (2005), p.

- Van der Toorn 1999, p. 911–3.

- Dunn and Rogerson, pp.153–154

- Avery Peck, p.58

- Grabbe (2004), pp. 243-244

- Avery Peck, p.59

Bibliography

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume II: From the Exile to the Maccabees. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Albertz, Rainer (2003a). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Albertz, Rainer; Becking, Bob, eds. (2003b). Yahwism After the Exile: Perspectives on Israelite Religion in the Persian Era. Koninklijke Van Gorcum. Becking, Bob. "Law as Expression of Religion (Ezra 7–10)".

- Amit, Yaira, et al., eds. (2006). Essays on Ancient Israel in its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Na'aman. Eisenbrauns.

- Avery-Peck, Alan, et al., eds. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Judaism. Blackwell. Murphy, Frederick J. R. "Second Temple Judaism".

- Barstad, Hans M. (2008). History and the Hebrew Bible. Mohr Siebeck.

- Becking, Bob, ed. (2001). Only One God? Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. Sheffield Academic Press. Dijkstra, Meindert. "El the God of Israel, Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism". Dijkstra, Meindert. "I Have Blessed You by Yahweh of Samaria and His Asherah: Texts with Religious Elements from the Soil Archive of Ancient Israel".

- Becking, Bob; Korpel, Marjo Christina Annette, eds. (1999). The Crisis of Israelite Religion: Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-Exilic Times. Brill. Niehr, Herbert. Religio-Historical Aspects of the Early Post-Exilic Period.

- Bedford, Peter Ross (2001). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Brill.

- Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39731-2.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1988). Ezra-Nehemiah: A Commentary. Eerdmans.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph; Lipschits, Oded, eds. (2003). Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Eisenbrauns. Blenkinsopp, Joseph. "Bethel in the Neo-Babylonian Period". Lemaire, Andre. "Nabonidus in Arabia and Judea During the Neo-Babylonian Period".

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans.

- Bloch-Smith, Elizabeth (2008). "Bible, Archaeology, and the Social Sciences". In Frederick E. Greenspahn. The Hebrew Bible: new insights and scholarship. NYU Press.

- Brett, Mark G. (2002). Ethnicity and the Bible. Brill. Edelman, Diana. "Ethnicity and Early Israel".

- Bright, John (2000; 4th ed., 1st ed. 1959). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Coogan, Michael D., ed. (1998). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. Stager, Lawrence E. "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel".

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.

- Coote, Robert B.; Whitelam, Keith W. (1986). "The Emergence of Israel: Social Transformation and State Formation Following the Decline in Late Bronze Age Trade". Semeia (37): 107–47.

- Davies, Philip R. (1992). In Search of Ancient Israel. Sheffield.

- Davies, Philip R. (2009). "The Origin of Biblical Israel". Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 9 (47).

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans.

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans.

- Dever, William (2005). Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans.

- Dunn, James D.G; Rogerson, John William, eds. (2003). Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. Rogerson, John William. "Deuteronomy".

- Edelman, Diana, ed. (1995). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Kok Pharos.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Mazar, Amihay; Schmidt, Brian B. (2007). The Quest for the Historical Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. Mazar, Amihay. "The Divided Monarchy: Comments on Some Archaeological Issues".

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004a). Ancient Canaan and Israel: An Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004b). Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO.

- Goodison, Lucy; Morris, Christine (1998). Goddesses in Early Israelite Religion in Ancient Goddesses: The Myths and the Evidence. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. T&T Clark International.

- Grabbe, Lester L., ed. (2008). Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIa (c. 1250–850 B.C.E.). T&T Clark International.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature.

- King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22148-3.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BCE. Routledge.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Levy, Thomas E. (1998). The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing. LaBianca, Øystein S.; Younker, Randall W. "The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (c. 1400–500 CE)".

- Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem. Eisenbrauns.

- Lipschits, Oded, et al., eds. (2006). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. Kottsieper, Ingo. "And They Did Not Care to Speak Yehudit".Lipschits, Oded; Vanderhooft, David. "Yehud Stamp Impressions in the Fourth Century B.C.E.".

- Liverani, Mario (2005). Israel's History and the History of Israel, London, Equinox.

- Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press.

- Mays, James Luther, et al., eds. (1995). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clarke.Miller, J. Maxwell. "The Middle East and Archaeology".

- McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Merrill, Eugene H. (1995). "The Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Transition and the Emergence of Israel". Bibliotheca Sacra. 152 (606): 145–62.

- Middlemas, Jill Anne (2005). The Troubles of Templeless Judah. Oxford University Press.

- Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-21262-X.

- Miller, Robert D. (2005). Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries B.C. Eerdmans.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans.

- Nodet, Étienne (1999) [Editions du Cerf 1997]. A Search for the Origins of Judaism: From Joshua to the Mishnah. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Pitkänen, Pekka (2004). "Ethnicity, Assimilation and the Israelite Settlement"(PDF). Tyndale Bulletin. 55 (2): 161–82.

- Silberman, Neil Asher; Small, David B., eds. (1997). The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present. Sheffield Academic Press. Hesse, Brian; Wapnish, Paula. "Can Pig Remains Be Used for Ethnic Diagnosis in the Ancient Near East?".

- Smith, Mark S. (2001). Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century. Hendrickson Publishers.

- Smith, Mark S.; Miller, Patrick D. (2002) [Harper & Row 1990]. The Early History of God. Eerdmans.

- Rendsburg, Gary (2008). "Israel without the Bible". In Frederick E. Greenspahn.The Hebrew Bible: new insights and scholarship. NYU Press.

- Soggin, Michael J. (1998). An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. Paideia.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (1992). Early History of the Israelite People. Brill.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel. Brill.

- Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999).Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2d ed.). Koninklijke Brill.

- Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E., eds. (1992). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Sheffield. Cahill, Jane M. "Jerusalem at the Time of the United Monarchy". Lehman, Gunnar. "The United Monarchy in the Countryside".

- Wylen, Stephen M. (1996). The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction. Paulist Press.

- Zevit, Ziony (2001). The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. Continuum.

Further reading

- Avery-Peck, Alan, and Neusner, Jacob, (eds), "The Blackwell Companion to Judaism (Blackwell, 2003)

- Brettler, Marc Zvi, "The Creation of History in Ancient Israel" (Routledge, 1995), and also review at Dannyreviews.com

- Cook, Stephen L., "The social roots of biblical Yahwism" (Society of Biblical Literature, 2004)

- Day, John (ed), "In search of pre-exilic Israel: proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar" (T&T Clark International, 2004)

- Gravett, Sandra L., "An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible: A Thematic Approach" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

- Grisanti, Michael A., and Howard, David M., (eds), "Giving the Sense:Understanding and Using Old Testament Historical Texts" (Kregel Publications, 2003)

- Hess, Richard S., "Israelite religions: an archaeological and biblical survey" Baker, 2007)

- Kavon, Eli, "Did the Maccabees Betray the Hanukka Revolution?", The Jerusalem Post, 26 December 2005

- Lemche, Neils Peter, "The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

- Levine, Lee I., "Jerusalem: portrait of the city in the second Temple period (538 B.C.E.–70 C.E.)" (Jewish Publication Society, 2002)

- Na'aman, Nadav, "Ancient Israel and its neighbours" (Eisenbrauns, 2005)

- Penchansky, David, "Twilight of the gods: polytheism in the Hebrew Bible" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2005)

- Provan, Iain William, Long, V. Philips, Longman, Tremper, "A Biblical History of Israel" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2003)

- Russell, Stephen C., "Images of Egypt in early biblical literature" (Walter de Gruyter, 2009)

- Sparks, Kenton L., "Ethnicity and identity in ancient Israel" (Eisenbrauns, 1998)

- Stackert, Jeffrey, "Rewriting the Torah: literary revision in Deuteronomy and the holiness code" (Mohr Siebeck, 2007)

- Vanderkam, James, "An introduction to early Judaism" (Eerdmans, 2001)

e

The Book of Joshua or Book of Jehoshua (Hebrew: ספר יהושע Sefer Yĕhôshúa) is the sixth book in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its 24 chapters tell of the Israelite invasion of Canaan,[1] their conquest and division of the land under the leadership of Joshua, and of serving God in the land.[2] Joshua forms part of the biblical account of the emergence of Israel, which begins with the exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, continues with the book of Joshua, and culminates in the Book of Judges with the conquest and settlement of the land.[3]

The book is in two roughly equal parts. The first part depicts the campaigns of the Israelites in central, southern and northern Canaan, as well as the destruction of their enemies. The second part details the division of the conquered land among the twelve tribes. The two parts are framed by set-piece speeches by God and Joshua commanding the conquest and at the end warning of the need for faithful observance of the Law (torah) revealed to Moses.[4]

Almost all scholars agree that the book of Joshua holds little historical value for early Israel and most likely reflects a much later period.[5] Although Rabbinic tradition holds that the book was written by Joshua, it is probable that it was written by multiple editors and authors far removed from the times it depicts.[6] The earliest parts of the book are possibly chapters 2–11, the story of the conquest; these chapters were later incorporated into an early form of Joshua written late in the reign of king Josiah (reigned 640–609 BCE), but the book was not completed until after the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 586, and possibly not until after the return from the Babylonian exile in 539.[7]

Contents

Structure

I. Transfer of leadership to Joshua (1:1–18)

- B. Joshua's instructions to the people (1:10–18)

II. Entrance into and conquest of Canaan (2:1–5:15)

- A. Entry into Canaan

- 1.Reconnaissance of Jericho (2:1–24)

- 2. Crossing the River Jordan (3:1–17)

- 3. Establishing a foothold at Gilgal (4:1–5:1)

- 4. Circumcision and Passover (5:2–15)

- B. Victory over Canaan (6:1–12:24)

- 1. Destruction of Jericho (6)

- 2. Failure and success at Ai (7:1–8:29)

- 3. Renewal of the covenant at Mount Ebal (8:30–35)

- 4. Other campaigns in central Canaan(9:1–27)

- 5. Campaigns in southern Canaan (10:1–43)

- 6. Campaigns in northern Canaan(11:1–23)

- 7. Summary list of defeated kings (12:1–24)

III. Division of the land among the tribes (13:1–22:34)

- A. God's instructions to Joshua (13:1–7)

- B. Tribal allotments (13:8–19:51)

- 1. Eastern tribes (13:8–33)

- 2. Western tribes (14:1–19:51)

- C. Cities of refuge and levitical cities (20:1–21:42)

- D. Summary of conquest (21:43–45)

- E. Dismissal of the eastern tribes (serving YHWH in the land) (22:1–34)

IV. Conclusion (23:1–24:33)

- A. Joshua's farewell address (23:1–16)

- B. Covenant at Shechem (24:1–28)

- C. Deaths of Joshua and Eleazar; burial of Joseph's bones (24:29–33)[4]

Summary

God's commission to Joshua (chapter 1)

Chapter 1 presents the first of three important moments in Joshua marked with major speeches and reflections by the main characters; here first God and then Joshua make speeches about the goal of conquest of the Promised Land; at chapter 12, the narrator looks back on the conquest; and at chapter 23 Joshua gives a speech about what must be done if Israel is to live in peace in the land).[8]

God commissions Joshua to take possession of the land and warns him to keep faith with the Covenant. God's speech foreshadows the major themes of the book: the crossing of the Jordan and conquest of the land, its distribution, and the imperative need for obedience to the Law; Joshua's own immediate obedience is seen in his speeches to the Israelite commanders and to the Transjordanian tribes, and the Transjordanians' affirmation of Joshua's leadership echoes Yahweh's assurances of victory.[9]

Entry into the land and conquest (chapters 2–12)

The Israelites cross the Jordan through the miraculous intervention of God and theArk of the Covenant and are circumcised at Gibeath-Haaraloth (translated as hill of foreskins), renamed Gilgal in memory (Gilgal sounds like Gallothi, I have removed, but is more likely to translate as circle of standing stones). The conquest begins in Canaan with Jericho, followed by Ai (central Canaan), after which Joshua builds an altar to Yahweh at Mount Ebal (northern Canaan) and renews the Covenant. The covenant ceremony has elements of a divine land-grant ceremony, similar to ceremonies known from Mesopotamia.[10]

The narrative then switches to the south. The Gibeonites trick the Israelites into entering into an alliance with them by saying they are not Canaanites; this prevents the Israelites from exterminating them, but they are enslaved instead. An alliance ofAmorite kingdoms headed by the Canaanite king of Jerusalem is defeated withYahweh's miraculous help, and the enemy kings are hanged on trees. (The Deuteronomist author may have used the then-recent 701 BCE campaign of theAssyrian king Sennacherib in Judah as his model; the hanging of the captured kings is in accordance with Assyrian practice of the 8th century).[11]

With the south conquered the narrative moves to the northern campaign. A powerful multi-national (or more accurately, multi-ethnic) coalition headed by the king of Hazor, the most important northern city, is defeated with Yahweh's help and Hazor captured and destroyed. Chapter 11:16–23 summarises the campaign: Joshua has taken the entire land, and the land "had rest from war." Chapter 12 lists the vanquished kings on both sides of the Jordan.

Division of the land (chapters 13–21)

Having described how the Israelites and Joshua have carried out the first of their God's commands, the story now turns to the second, to "put the people in possession of the land." This section is a "covenantal land grant": Yahweh, as king, is issuing each tribe its territory.[12] The "cities of refuge" and Levitical cities are attached to the end, since it is necessary for the tribes to receive their grants before they allocate parts of it to others. The Transjordanian tribes are dismissed, affirming their loyalty to Yahweh.

The book describes how Joshua divided the newly conquered land of Canaan into parcels, and assigned them to the Tribes of Israel by lot.[13] The description serves a theological function to show how the promise of the land was realized in the biblical narrative; its origins are unclear, but the descriptions may reflect geographical relations among the places named.[14] :5

Joshua's farewell (chapters 22–24)

Joshua charges the leaders of the Israelites to remain faithful to Yahweh and the covenant, warning of judgement should Israel leave Yahweh and follow other gods; Joshua meets with all the people and reminds them of Yahweh's great works for them, and of the need to love Yahweh alone. Joshua performs the concluding covenant ceremony, and sends the people to their inheritance.

Composition

The Taking of Jericho (Jean Fouquet, c.1452–1460)

The Book of Joshua is anonymous. TheBabylonian Talmud, written in the 3rd to 5th centuries CE, was the first attempt to attach authors to the holy books: each book, according to the authors of the Talmud, was written by a prophet, and each prophet was an eyewitness of the events described, and Joshua himself wrote "the book that bears his name". This idea was rejected as untenable by John Calvin (1509–1564), and by the time of Thomas Hobbes(1588–1679) it was recognised that the book must have been written much later than the period it depicted.[15]

There is now general agreement that Joshua was composed as part of a larger work, the Deuteronomistic history, stretching fromDeuteronomy to Kings.[16] In 1943 the German biblical scholar Martin Nothsuggested that this history was composed by a single author/editor, living in the time of the Exile (6th century BCE).[17] A major modification to Noth's theory was made in 1973 by the American scholar Frank M. Cross, to the effect that two editions of the history could be distinguished, the first and more important from the court of king Josiah in the late 7th century, and the second Noth's 6th century Exilic history.[18] Later scholars have detected more authors or editors than either Noth or Cross allowed for.[19]

Themes and genre

Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gideon (John Martin)

Historical and archaeological evidence

The prevailing scholarly view is that Joshua is not a factual account of historical events.[20] The apparent setting of Joshua is the 13th century BCE;[20] this was a time of widespread city-destruction, but with a few exceptions (Hazor, Lachish) the destroyed cities are not the ones the Bible associates with Joshua, and the ones it does associate with him show little or no sign of even being occupied at the time.[21]

Given its lack of historicity, Carolyn Pressler, in a recent commentary for the Westminster Bible Companion series, suggests that readers of Joshua should give priority to its theological message ("what passages teach about God") and be aware of what these would have meant to audiences in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE.[22]Richard Nelson explains: The needs of the centralised monarchy favoured a single story of origins combining old traditions of an exodus from Egypt, belief in a national god as "divine warrior," and explanations for ruined cities, social stratification and ethnic groups, and contemporary tribes.[23]

Themes

The overarching theological theme of the Deuteronomistic history is faithfulness (and its opposite, faithlessness) and God's mercy (and its obverse, his anger). In Judges, Samuel, and Kings, Israel becomes faithless and God ultimately shows his anger by sending his people into exile,[24] but in Joshua Israel is obedient, Joshua is faithful, and God fulfills his promise and gives them the land.[25] Yahweh's war campaign in Canaan validates Israel's entitlement to the land[26] and provides a paradigm of how Israel was to live there: twelve tribes, with a designated leader, united by covenant in warfare and in worship of Yahweh alone at single sanctuary, all in obedience to the commands of Moses as found in Deuteronomy.[27]

God and Israel

Joshua takes forward Deuteronomy's theme of Israel as a single people worshiping Yahweh in the land God has given them.[28] Yahweh, as the main character in the book, takes the initiative in conquering the land, and it is Yahweh's power that wins battles (for example, the walls of Jericho fall because Yahweh is fighting for Israel, not because the Israelites show superior fighting ability).[29] The potential disunity of Israel is a constant theme, the greatest threat of disunity coming from the tribes east of the Jordan, and there is even a hint in chapter 22:19 that the land across the Jordan is unclean and the tribes who live there are of secondary status.[30]

Land

Land is the central topic of Joshua.[31] The introduction to Deuteronomy recalled how Yahweh had given the land to the Israelites but then withdrew the gift when Israel showed fear and only Joshua and Caleb had trusted in God.[32] The land is Yahweh's to give or withhold, and the fact that he has promised it to Israel gives Israel an inalienable right to take it. For exilic and post-exilic readers, the land was both the sign of Yahweh's faithfulness and Israel's unfaithfulness, as well as the centre of their ethnic identity. In Deuteronomistic theology, "rest" meant Israel's unthreatened possession of the land, the achievement of which began with the conquests of Joshua.[33]

The enemy

Joshua "carries out a systematic campaign against the civilians of Canaan — men, women and children — that amounts to genocide."[34] In doing this he is carrying outherem as commanded by Yahweh in Deuteronomy 20:17: "You shall not leave alive anything that breathes." The purpose is to drive out and dispossess the Canaanites, with the implication that there are to be no treaties with the enemy, no mercy, and no intermarriage.[9] This purpose is further supported by the implication that Yahweh would send a plague of hornets to wherever Israel's campaign would bring them to next, resulting in the majority of the Canaanite people being displaced rather than caught up in the slaughter when the Israelites arrived. See Exodus 23:28 and Deuteronomy 7:20. "The extermination of the nations glorifies Yahweh as a warrior and promotes Israel's claim to the land," while their continued survival "explores the themes of disobedience and penalty and looks forward to the story told in Judges and Kings."[35] The divine call for massacre at Jericho and elsewhere can be explained in terms of cultural norms (Israel wasn't the only Iron Age state to practice here) and theology (a measure to ensure Israel's purity as well as the fulfillment of God's promise),[9] but Patrick D. Miller in his commentary on Deuteronomy remarks, "there is no real way to make such reports palatable to the hearts and minds of contemporary readers and believers."[36]

Obedience

Obedience vs. disobedience is a constant theme.[37] Obedience ties in the Jordan crossing, the defeat of Jericho and Ai, circumcision and Passover, and the public display and reading of the Law. Disobedience appears in the story of Achan (stoned for violating the herem command), the Gibeonites, and the altar built by the Transjordan tribes. Joshua's two final addresses challenge the Israel of the future (the readers of the story) to obey the most important command of all, to worship Yahweh and no other gods. Joshua thus illustrates the central Deuteronomistic message, that obedience leads to success and disobedience to ruin.[38]

Moses, Joshua and Josiah

The Deuteronomistic history draws parallels in proper leadership between Moses, Joshua and Josiah.[39] God's commission to Joshua in chapter 1 is framed as a royal installation, the people's pledge of loyalty to Joshua as successor Moses recalls royal practices, the covenant-renewal ceremony led by Joshua was the prerogative of the kings of Judah, and God's command to Joshua to meditate on the "book of the law" day and night parallels the description of Josiah in 2 Kings 23:25 as a king uniquely concerned with the study of the law — not to mention their identical territorial goals (Josiah died in 609 BCE while attempting to annex the former Israel to his own kingdom of Judah).[40]

Some of the parallels with Moses can be seen in the following, and not exhaustive, list:[16]

- Joshua sent spies to scout out the land near Jericho (2:1), just as Moses sent spies from the wilderness to scout out the Promised Land (Num. 13; Deut. 1:19–25).

- Joshua led the Israelites out of the wilderness into the Promised Land, crossing the Jordan River as if on dry ground (3:16), just as Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt through the Red Sea, which they crossed as if on dry land (Ex. 14:22).

- After crossing the Jordan River, the Israelites celebrated the Passover (5:10–12) just as they did immediately before the Exodus (Ex. 12).

- Joshua's vision of the "commander of Yahweh's army" (5:13–15) is reminiscent of the divine revelation to Moses in the burning bush (Ex. 3:1–6).

- Joshua successfully intercedes on behalf of the Israelites when Yahweh is angry for their failure to fully observe the "ban" (herem), just as Moses frequently persuaded God not to punish the people (Ex. 32:11–14, Num. 11:2, 14:13–19).

- Joshua and the Israelites were able to defeat the people at Ai because Joshua followed the divine instruction to extend his sword (Josh 8:18), just as the people were able to defeat the Amalekites as long as Moses extended his hand that held "the staff of God" (Ex. 17:8–13).

- Joshua served as the mediator of the renewed covenant between Yahweh and Israel at Shechem (8:30–35; 24), just as Moses was the mediator of Yahweh's covenant with the people at Mount Sinai/Mount Horeb.

- Before his death, Joshua delivered a farewell address to the Israelites (23–24), just as Moses had delivered his farewell address (Deut. 32–33).

See also

References

- Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary | Freedman, D. N., Herion, G. A., Graf, D. F., Pleins, J. D., & Beck, A. B. (Eds.). (1992) | New York: Doubleday. | Book of Joshua

- McConville (2001), p.158

- McNutt, p.150

- Achtemeier and Boraas

- Killebrew, pp.152

- Creach, pp.9–10

- Creach, pp.10–11

- De Pury, p.49

- Younger, p.175

- Younger, p.180

- Na'aman, p.378

- Younger, p.183

- "JOSHUA, BOOK OF - JewishEncyclopedia.com".

- Dorsey, David A. (1991). The Roads and Highways of Ancient Israel. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3898-3.

- De Pury, pp.26–30

- Younger, p.174

- Klein, p.317

- De Pury, p.63

- Knoppers, p.6

- McConville (2010), p.4

- Miller&Hayes, pp. 71–2.

- Pressler, pp.5–6

- Nelson, p.5

- Laffer, p.337

- Pressler, pp.3–4

- McConville (2001), pp.158–159

- Coogan 2009, p. 162.

- McConville (2001), p.159

- Creach, pp.7–8

- Creach, p.9

- McConville (2010), p.11

- Miller (Patrick), p.33

- Nelson, pp.15–16

- Dever, p.38

- Nelson, pp.18–19

- Miller (Patrick), pp.40–41

- Curtis, p.79

- Nelson, p.20

- Nelson, p.102

- Finkelstein, p.95

Bibliography

Translations of Joshua

Commentaries on Joshua

- Auzou, Georges (1964). Le Don d'une conquête: étude du livre de Josué (in series, Connaissance de la Bible, 4). Éditions de l'Orante.

- Creach, Jerome F.D (2003). Joshua. Westminster John Knox Press.ISBN 9780664237387.

- Curtis, Adrian H.W (1998). Joshua. Sheffield Academic Press.ISBN 9781850757061.

- Harstad, Adolph L. (2002). Joshua (in series, Concordia Commentary). Arch Books. ISBN 978-0-570-06319-3.

- McConville, Gordon; Williams, Stephen (2010). Joshua. Eerdmans.ISBN 9780802827029.

- McConville, Gordon (2001). "Joshua". In John Barton; John Muddiman. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Miller, Patrick D (1990). Deuteronomy. Cambridge University Press.ISBN 9780664237370.

- Nelson, Richard D (1997). Joshua. Westminster John Knox Press.ISBN 9780664226664.

- Pressler, Carolyn (2002). Joshua, Judges and Ruth. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664255268.

- Younger, K. Lawson Jr (2003). "Joshua". In James D. G. Dunn; John William Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans.ISBN 9780802837110.

General

- Achtemeier, Paul J; Boraas, Roger S (1996). The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Bright, John (2000). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.ISBN 9780664220686.

- Campbell, Anthony F (1994). "Martin Noth and the Deuteronomistic History". In Steven L. McKenzie; Matt Patrick Graham. The history of Israel's traditions: the heritage of Martin Noth. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567230355.

- Campbell, Anthony F; O'Brien, Mark (2000). Unfolding the Deuteronomistic history: origins, upgrades, present text. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413687.

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780826468307.

- De Pury, Albert; Romer, Thomas (2000). "Deuteronomistic Historiography (DH): History of Research and Debated Issues". In Albert de Pury; Thomas Romer; Jean-Daniel Macchi. Israël constructs its history: Deuteronomistic historiography in recent research. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567224156.

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802809759.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed. Free Press.ISBN 9780743223386.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830974.

- Klein, R.W. (2003). "Samuel, books of". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. The international standard Bible encyclopedia. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837844.

- Knoppers, Gary (2000). "Introduction". In Gary N. Knoppers; J. Gordon McConville.Reconsidering Israel and Judah: recent studies on the Deuteronomistic history. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060378.

- Laffey, Alice L (2007). "Deuteronomistic history". In Orlando O. Espín; James B. Nickoloff. An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658567.

- McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664222659.

- Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-21262-X.

- Naʾaman, Nadav (2005). Ancient Israel and Its Neighbors: Collected Essays: Volume 2. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061139.

- Van Seters, John (2000). "The Deuteronomist from Joshua to Samuel". In Gary N. Knoppers; J. Gordon McConville. Reconsidering Israel and Judah: Recent Studies on the Deuteronomistic History. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060378.

Tribal allotments of Israel: Books and maps

- Abu-Sitta, Salman H. (2004). Atlas of Palestine, 1948. Palestine Land Society.

- Aharoni, Yohanan (1979). The Land of the Bible; A Historical Geography. The Westminster Press. ISBN 0-664-24266-9.

- Campbell, E., Jr. (1991). Shechem II. ASOR. ISBN 0-89757-062-6.

- Dever, William G. (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0975-8.

- Finkelstein, I. and Z. Lederman (eds.) (1997). Highlands of Many Cultures: The Southern Samaria Survey. Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology. ISBN 965-440-007-3.

- Curtis, Adrian (2009). Oxford Bible Atlas, Fourth Edition. Oxford University Press.ISBN 9780199560462.

- Kallai, Zecharia (1986). Historical Geography of the Bible; The Tribal Territories of Israel. The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University. ISBN 965-223-631-4.

- Miller, Robert D., II, (2005). Chieftains Of The Highland Clans: A History Of Israel In The Twelfth And Eleventh Centuries B.C. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0988-X.

- Na'aman, Nadav (1986). Borders and Districts in Biblical Historiography. Simor, Ltd. ISBN 965-242-005-0.

External links

- Original text

- יְהוֹשֻׁעַ Yehoshua–Joshua (Hebrew–English at Mechon-Mamre.org, Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Jewish translations

- Joshua (Judaica Press) translation with Rashi's commentary at chabad.org

- Christian translations

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

- Joshua at Wikisource (Authorised King James Version)

Joshua public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Joshua public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

No comments:

Post a Comment